Before MP3’s, before streaming, before laptop recording software, there were records and there was radio.

From the church or the club, performers might make it lucky and get on the radio. Maybe then they would be offered the chance to make a record. If the record did something locally you might hit the road, playing night after night, concerts promoting the records, records promoting concert appearances; the ouroboros of the stardom machine.

In the 1940’s a new hustle emerged in the form of the independent recording studio. Technical innovations like magnetic tape recording and multi-tracking made higher fidelity possible at a lower cost. Studios sprung up in cities across the country.

These studios were a big step towards the democratization we see in the recording industry today. For the first time, the local singer, guitar picker, or church choir could immortalize themselves on a record that they paid to have recorded. Small-time independent record labels followed by the hundreds. The possibility of fortune and fame enticed many and kicked off a proliferation of performers.

Mark V Studios of Greenville, South Carolina was one of these early independent studios. First organized in 1961, Mark V recorded the sounds of the south for the next thirty years.

The studio’s first location was in the middle of Greenville’s Unity Park. Three brothers named Huffman; Harold, Bill, and Joe, rented a building at 78 Mayberry Street. The brothers had learned to play together listening to Merle Travis, Chet Atkins, and Spartanburg native Hank Garland.

“If you weren’t those three people you didn’t play guitar, in our minds,” said Joe Huffman. The admiration for Garland was particularly apparent. “Nobody plays with the speed, with the quality of tone and the beautiful melodic line (he plays with). A lot of people can play a lot of notes, but he never left you guessing where he was in the melody.”

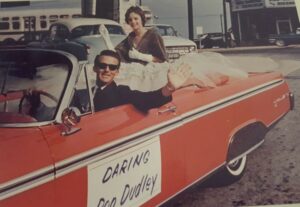

The Huffman brothers influences show. They emerged on the music scene in Greenville while they were yet schoolboys. Bill and Harold played in outfits led by two DJ’s from WESC who played the records the kids were wild about. Earl Baughman with his Gospel Train and Country Earl shows had a band called the Circle E Ranch Boys.Floyd Edge took the alias Don Dudley for his Uncle Dudley program and fronted a band called the Tunetoppers. These groups were hep to what was happening. There is a photo of Country Earl with Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana, two of Elvis Presley’s bandmates. But don’t tell Bill Huffman they were playing rock’n’roll.

“Country,” he corrected me. “Little Jimmy Dickens country.”

Having proven themselves on stage, the young musicians marshalled all their money and rented the spot on Mayberry with the hope of recording their own playing. Bill and Harold went off to Atlanta to pick up some used Ampex recording equipment. They had keys to a place where they could play all night. That was all they cared about, then.

Their other brother, Sam, owned the Carolina Plating Company out on Highway 253. He lent the guys a little money (with interest) at the start. Sam’s neighbor at the plating company was a man named Robert Rigby. Rigby was an electrical engineer who had done some work with the father of the electric guitar, Les Paul. Through this fortuitous alignment the boy’s technological ambitions grew from the glorified rehearsal space they had imagined.

They found a console that had suffered some damage in a fire at radio station WSPA. They had it cleaned up and it sounded good. Their building had been a radio studio, so their two-channel mixer could be bounced from the left to the right studios. A control booth looked onto both rooms.

In the early ‘60’s the recording industry was switching over from monaural to stereophonic recording. FM radio is broadcast in stereo and it was expanding. Many of the major labels released mono and stereo versions of albums to accommodate consumers who had not yet made the switch.

The brother’s endeavor had attracted the attention of Don Dudley, the DJ, by this time. In fact, it was he who located the burned-up console. Anticipating the shift to stereo, Dudley and the Huffman’s came up with ingenious methods of using their ragtag equipment.They drew on the work of Les Paul, with instruction from Robert Rigby, to overcome some of their technical challenges.

“Dudley was a DJ, so he had worked the WESC console. He knew how the buttons worked, but he was also figuring it out as he went along.” recalls Joe. “But the first thing we did was re-wire the console because it was monaural, which means you only had one output. And we knew that stereo was on its way.”

“What we did, we took that radio console that had the left and the right for the two different studios and we made it so the feed would go from left to right. So, it would be on the left track or the right track on stereo. We used that as our direction for sending it out to the tape machine in stereo,” Bill explains.

“Now, we didn’t have a stereo machine at that point. But the way we used it was, we had two mono machines. So, we ‘d record on the first machine and then add the mic of the guy doing a vocal overdub on the other mono machine. Then we’d put both tracks over to the second machine. But we still had to have that stereo console that would give us another output. That was Les Paul’s original concept, how he started building multi-track recordings to overdub his guitar.”

The Huffman brothers also devised a way to turn a normal tape player into a device to create an echo effect for their recordings. Then, by adjusting the interval of the echo, the space between sounds, they could play music back at slower speeds without losing the pitch of the recording. This way, they could listen to Hank Garland’s guitar solos note for note and learn his techniques.

“That allowed us to look inside of his playing,” explains Joe.

“We would sit into the middle of the night learning how to play one groove on the record, just to get that one lick right,” remembers Bill

Bill, Harold, and Joe had a harrowing experience when they built an echo chamber in the new studio. Bill tells the story.

“We were listening to records and trying to figure out how they got that perfect sound. We decided that a good echo system was it. So, me and Harold and Joe went into the basement of that little radio station, and we built our own echo chamber. It was sixteen feet long and three feet wide and we figure it out so all the angles were like they should be. We had that room airtight. Anyway, me and stupid there got in there with that epoxy paint.”

“And the more we painted the happier we got,” Joe interjects. “We could have died. We would have just gone on echoing in there with everything else. We often wonder who was looking out for us.”

Gospel Quartets

The quartet style of gospel music ran deep in Greenville in those days. Greenville native Hovie Lister fronted the Statesmen, a group that made a huge name for themselves through the ‘50’s by peppering their gospel performances with swinging rhythms. The Stamps Quartet was in its fourth decade when the powerful bassist JD Sumner took the helm in the ‘60’s. Some say Sumner was Elvis’ favorite singer. The National Quartet Conventions started around this time and featured the Stamps and others, like the Blackwood Brothers and the Oak Ridge Boys, playing to huge crowds. Gospel quartet singing was a commercially proven form, and Greenville was buying.

The first group to come looking for a record from the Huffman brothers was local. In 1961 the Trav’lers were a young group. Pianist Otis Forrest was just nineteen years old, the oldest members only in their mid-twenties. The groups talent for harmonizing was already gaining recognition in the gospel music world, though, and they quickly established themselves as a draw among gospel quartet fans.

Their star shone so brightly that it caught the attention of a local wrestling promoter turned TV host. Bob Poole’s Gospel Favorites had the Trav’lers on to perform in 1961. The young group liked the reception they received so much that they went looking to make a record.

The group found out about the Huffman brothers’ studio and came to record their record The Trav’lers Sing Songs You Have Requested with the brothers and some other musicians they assembled backing and engineering. They did numbers that were hits from Bob Poole’s Gospel Favorites.

Even though no money changed hands for the Trav’lers sessions, the studio now looked to be viable as a commercial enterprise, and the Huffman brothers positioned themselves to attract clients right away. They became the house band on Bob Poole’s Gospel Favorites and got a plug from the host every week, in homes throughout the Southeast.

“Back then Poole had a sidekick, Bill Hefner. Hefner was with the group the Harvesters Quartet out of Charlotte. Hefner and Poole were kind of like Johnny Carson and Ed McMahon. Now, Bill Hefner would work it in where he would ask Bob Poole something like, “What do you think of our music.” And Poole would say something like, “I tell you what these old boys from Mark V can play. If you need any recording done you should go down and see these guys.”

The Huffman’s and Don Dudley dubbed their new enterprise Mark V Studios as a nod to the new Lincoln. The car is a sight to behold and, as Bill puts it, “We thought it sounded like quality.” They got off the ground with all the Greenville gospel groups after the Bob Poole appearances. They cemented a relationship with Horace Mauldin and his Mauldin Family Trio. Two of the Mauldin sons, Steve, and Russell would grow up at the studio and become staff musicians in their teens. Horace brought on talent from the Church of God denomination to record for his Melody Records.

Outside of gospel, Bill and Joe Huffman do not recall the particulars of the early records. They brush these of as “some country things we did.” But there is a definite shift in sound that seems to align with the move of Mark V from the Mayberry Street location to a new facility, designed by the studio’s art director Michael Burnette. The new shop on Michael Drive, off White Horse Road, is where the sound coming off the needle begins to be the polished, tight country twang that would put the studio in the vanguard of southern gospel. But some of the early 45’s, especially those on the Klub label, are more raucous affairs. The studio cut country and rock, as well as jazz and jingle records, throughout its existence. But a stylistic and technological change is apparent in the early 60’s.

It is interesting to note that, although Bill did not remember any of those early sides, his playing a part in them seems likely. He was playing in bands with Country Earl and Don Dudley. Dudley held a stake in the studio very briefly at the beginning, and he gets a producer credit on a whole bunch of rocking country 45’s from early ‘60’s Greenville. Perhaps some of these were players from the style that I called rockabilly and he insisted was “Little Jimmy Dickens country.” Records by Leonard Clark and The Land of Sky Boys and Ted Patterson and the Tunesters would certainly qualify. Bill was a guitarist for hire at the time, capable, and in a unique position to offer his services. It would be a greater coincidence if he had not played with these guys than if he had.

The change in sound is certainly due, in part, to a change in facilities and ever-improving equipment, but the musicians the Huffman’s had assembled by the time they reached Michael Drive made the difference. Bill and Joe are both gifted guitarists, and Harold a great bassist. But at the new studio they put together a band that could handle commercial charts and pick like the boys in Nashville. These players include Buster Phillips on drums, Larry Orr and Tommy Dodd playing pedal steel, the Huffman boys on guitars along with Pee Wee Melton and Mike Burnette. A little later Steve Mauldin would become session bassist while he studied music at Furman University. His brother Russell would follow his example, but as a drummer. Both Mauldin boys credit Trav’lers pianist and arranger Otis Forrest, who came onto the studio’s staff while it was still on Mayberry Street, as a mentor in their careers as orchestral arrangers.

This is by no means a comprehensive list. Many more instrumentalists, arrangers, singers, and producers performed in sessions at Mark V. With this crack group of musicians, soon all kinds of sounds were coming out of Mark V; soul music and rhythm and blues, pop and rock, country and bluegrass, orchestral and acapella arrangements. Music filtered in from the clubs, churches, and street corners. By the mid-1960’s Mark V Studios reflected the musical culture of the whole region; rural and urban, Black and White, young and old, spiritual and secular.

The engineers and musicians had to become very adaptable. The variety required the studio to stretch out from its country and gospel foundations. Players had to be able to grasp styles, rhythms, harmonic structures, and tones that might be unfamiliar to them, and they had to do it quickly and with creativity. Studio time and recording tape costs money.

“Both (Joe and I) have a hearing problem now, but a lot of our problem is selective hearing,” explains Bill. “We trained our ear for years in the studio. When a group would come in to record, they would bring songs we never heard before. Our job was to learn that song and come up with some good ideas to make that song what it wanted to be. And we only had thirty minutes or an hour to do it because you have to record a whole album.”

“You had to create and record at the same time,” Joe adds.

Mark V musicians and arrangers were routinely stretched far beyond their comfort zone. Steve Mauldin remembers an adventurous session that tested drummer Billy Reynolds.

“We had this guy who would come up from the Cayman Islands, called himself the Barefoot Man. He would come to South Carolina to record and take his tapes back to the Cayman Islands and sell them to American tourists as island music. He came in for a session and asked if our drummer could play reggae. We said, “Are you kidding, Billy Reynolds? We call him Billy” Reggae” Reynolds!”

“So (engineer) Bill Medlin went in and told Billy Reynolds they’d be cutting a reggae tune and Billy looked at him and said, “What is reggae?”

The dynamism required of the musicians at Mark V made them all alert, responsive and broad players uniquely suited for work in a professional recording studio. Many of the musicians would continue to career in the premier studios of Nashville and their performances achieve great commercial success.

Mark V and the Southern Gospel Sound Evolve

The quartet style of gospel singing goes back well beyond the famous groups of the 50’s and 60’s. Its origins are in the shape note singing of the 19th century. James D. Vaughn, a graduate of the Ruebush Kieffer Normal school of shape-note music, began forming southern gospel quartets in 1910. These groups traveled the country promoting the songbooks of the James D. Vaughn Music Publishing Company. Out of these quartets came some of the biggest names in the southern gospel tradition. Virgil O. Stamps was a Vaughn alumnus who first fronted the long-running Stamps Quartet. Ben Speer started his career with a Vaughn quartet before starting the celebrated Speer Family quartet.

Quartets up until the 60’s had not featured much musical accompaniment. The Statesmen had Hovie Lister on piano, the Chuck Wagon Gang had a guitar, but the harmonizing vocalists were the focus. The Mark V band’s appearances on Bob Poole’s Gospel Favorites helped set a change in motion.

“That show was in syndication in six hundred plus stations across the country. This started happening on a weekly basis. Well, the groups that were coming on Bob Poole started saying, “while we’re in Greenville, why don’t we do our record at Mark V.”

“They wanted that music,” interjects Bill.

In the early ‘60’s pianist Jack Clark was a member of the popular Harvesters Quartet. The Harvesters came to record at Mark V shortly after that first Trav’lers session. Clark remembers being aware of the studio’s reputation for good musicianship, even in those early days.

“Mark V was turning out some good work. Not only did they have a good studio and turn out good product, but they had those musicians who could work as sidemen on those sessions. It really enhanced the sound of whoever recorded with them.”

Popular quartets like the Blue Ridge Quartet of Spartanburg, SC, the Rebels from Tampa, Fla, and the Couriers from Harrisburg, PA., began to record at Mark V.

As these group began to include backing musicians on their recordings, opinions slowly shifted on what was acceptable in gospel music.

“(In the early ‘60’s) nobody took anything other than a piano player out on the road with them,” Jack Clark explains. “In the mid-60’s we started adding bass and then, slowly, we started adding drums. The first drummers would come on stage with nothing but a snare drum and a set of brushes.”

As this shift happened, the Mark V band became established as one of the premier bands to accompany southern gospel quartets. They began to have a national profile, backing up some of the biggest groups on some of the hottest tickets.

By 1967 the band at Mark V was known as a powerhouse group. The studio was cranking out a record every week and gaining the attention of some of the genre’s biggest names. There was some resistance to the new sound from some of these established acts, though.

The first National Quartet Convention was held in 1957. The convention was started by J.D. Sumner and the Stamps Quartet and the Blackwood Brothers Quartet. By the mid-60’s the Convention had settled in Memphis, TN and was drawing crowds of up to 20,000 southern gospel fans.

“We were doing something with J.D. Sumner, and I asked him, “why don’t you let us be the staff musicians on the National Quartet Convention.” Joe Huffman recalls.” He said okay, and I said, “one caveat; I want to bring a drummer on with us.” J.D. said, “You got to be kidding. You’re going to get us all sent to hell.” But I told him it would be mild, just a snare and some brushes. J.D. said we could try it and, if it doesn’t work after the first song, we will pull the drummer off.”

A big drum kit was unusual on country music stages at this time, not to mention gospel. Even Grand Old Opry shows had yet to feature drums. But the audiences and musicians at the National Quartet Convention could not get enough of the new sound from the first bar. There was no turning back.

“After that first song nobody wanted to go onstage without us.” says Joe.

“We were only supposed to play with J.D. and the Stamps. We wound up playing with every quartet that came on that stage. Then they all came to the studio to record.” adds Bill.

As the 1960’s progressed southern gospel music continued to embrace the twangy, country sounds coming out of Mark V. Studio players like Buster Phillips, Pee Wee Melton, Steve and Russell Mauldin, and Joe Huffman carried this music into the studios of Nashville, and the country gospel sound they innovated weaved its way into mainstream taste on many country-tinged records of the 60’s and 70’s.

The Vanguard of 1960’s Southern Gospel

Through the late 60’s and 70’s Mark V, in alliance with Lefevre Sound in Atlanta, was the premier studio outside of Nashville for southern gospel music. Both studios cranked out a continuous stream of albums, week after week, year after year, during this period. Both studios kept a roster of musicians, arrangers and engineers employed. The Goss brothers: James, Lari, and Roni, worked at both and created a bond between the two organizations.

The music of the Goss brothers represented another strain in the progression of gospel music. They started out attempting to emulate the gospel quartet style, with brothers Lari and Roni singing baritone, a hired tenor and bass vocalist, and brother James on piano. Their vocals did not work well for the quartet style, though, and the group pared down their sound, carrying on with just the three brothers.

“I heard some recordings of that quartet we were doing recently. I tell you, if somebody brought that to me today, I still wouldn’t put it out,” says Roni Goss.

The sound the three Goss’s came up with in lieu of quartet singing was something new. With unique arrangements and original harmonic style, the Goss brothers began to represent the vanguard of southern gospel in the early 1960’s. They quickly won the admiration of fellow artists, although audiences were slower to come around.

“For a while we would play shows and have more people watching from behind than we did out in the seats. The other artists loved us, but we couldn’t get passed the first few rows out in the audience,” Roni recalls.

Maurice Lefevre’s family quartet was a stalwart group in the southern gospel community. His record label, Sing, operated out of Atlanta. In 1962, Sing released the Goss Brothers A New Concept in Gospel Singing album. The disc made a name for the Goss’s, and the they soon had all the work in the music business they could handle.

The success of New Concept convinced Lefevre to expand his business and start a recording studio in Atlanta. The Goss brothers became regulars on the staff at the new Lefevre Sound studio.

In Greenville, the Huffman brothers were among the musicians impressed by the Goss brothers’ new sound.

“The minute we heard the Goss Brothers,” remembers Joe Huffman, “we knew we needed to meet them, and we needed to work with them.”

The Huffman and Goss brothers soon became acquainted. The mutual admiration they shared brought Mark V together with Lefevre Sound in a relationship that helped both studios, and both families, to flourish artistically and professionally. Soon Joe Huffman was regularly traveling to Atlanta for sessions at Lefevre Sound and the Goss brothers were arranging, engineering, and performing on records at Mark V. The two studios formed a bridge from traditional gospel to the sound of the new that was taking off. The business relationship was fruitful, but the personal relationship and the musical synchronicity transcended business interests.

“It was a natural joining of minds and hearts, spirits and music,” says Joe Huffman. “We never had a plan. We just migrated to one another.”

In 1969 a fire ravaged Mark V Studios. Most of the equipment was destroyed and many artists lost the master recordings of their work.

The Mark V Studios family came together to rebuild after the fire. Musicians volunteered their time to help with cleanup and construction.

“Through the loyalty of the staff we were able to rebuild, or maybe even start over, you might call it,” remembers Bill Huffman. “The staff came together, and they didn’t play sessions, but they repaired and refurbished equipment while we were re-constructing the building. Part of us were working on the construction of the building, part of us were refurbishing equipment, looking for parts for the electronics. I think we were up and running again in a matter of months.”

The Goss brothers and Maurice Lefevre reached out to lend a hand in a way that only they could. Bill Huffman recalls their help with warmth.

“Maurice LeFevre, who you’d think would be a competitor, called up and said, “Guys, don’t miss a lick. My studio is yours. Bring your groups, do your work and keep things going as usual.” You never forget that kind of a relationship and we owe a special thanks to Maurice, by way of the Goss brothers.”

Many of the men and women who made music at Mark V share a bond of friendship to this day. A few years back Steve Mauldin organized a reunion for the studio’s musicians here in Greenville. Thirty years’ worth of performers showed up. Bill and Joe Huffman made a heartfelt presentation, along with Roni Goss. Tears of joy were shed. Some of the Trav’lers were there, Jack Clark from the Harvesters gave a speech. Even guys from the rock scene came, Butch Hendriks from the Tiki’s was there, and Will Hammond, who performed with the Uptowners and as The Invisible Burgundy Bullfrog and recorded singles for his Panther Records label at Mark V.

Mark V began as a hobby for a trio of guitar playing brothers. The Huffman brother’s dedication to musical quality and to the people who worked with them forged a bond of love, love for music and love for one another, that remains between many of the players today. The brothers have no lust for the limelight, their love is music. But one cannot help but grant them some quiet greatness for what they achieved with Mark V Studios.