The United House of Prayer for All People: The Music Academy for Greenville’s #1 Soul Legend

The Pendleton Street United House of Prayer for All People, Greenville, SC

I showered, shaved, and put on my old Brooks Brothers suit, grown tighter in the waist since I had last worn it. I looked normal enough in the mirror, but felt ridiculous. I had cleaned myself up to go experience the extraordinary music of the United House of Prayer for All People. House of Prayer (HOP) services are centered around the music of a large, trombone-heavy brass band that follows a cardiac beat set down by drums, tambourines, and the clapping hands of the congregation.

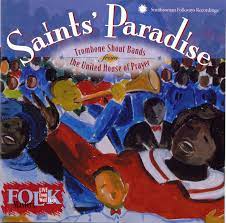

I had seen and heard inklings of this music on the internet. Articles have been written, few and far between. Smithsonian Folkways has released a compilation album. But none of my folk music, audiophile or jazz scholar friends knew much about it, and had certainly never experienced it first-hand. There is really nothing exotic or arcane about the church, though. They operate across the country, especially along the eastern seaboard. The church is not trying to keep their music a secret. But they are not advertising their talents, either. The purpose of the music is to bring the believers into one accord to make a joyful noise unto the Lord. So, to hear the music, I would have to join into the accord.

Folkways compilation of UHOP Shout Bands

In the sanctuary an old gentleman sat silent and alone. I took a pew in the back half of the cavernous room, constructed in an imitation of Gothic style. Linoleum tiles arranged in a colorful pattern adorned the floor. Some thirty rows of pews filled the sanctuary. A big box of tambourines sat near the altar and two banks of chairs were arranged, perpendicular to the pews, in front of the pulpit. A tuba leaned against the wall in the front corner. Photo portraits of the four Bishops of the denomination flanked the Holy Mountain, the name given to the pulpit in the House of Prayer.

An old woman named Ruth greeted me warmly and had me write my name on a sheet of yellow paper. I sat, awkward and unseemly. After a time, a man named Elder Smith took the stage and began to sing a low refrain. Gradually, the room became peopled, and a rhythm of handclaps joined his song. As they entered, a few hugs and waves were shared about the room, but no formal commencement to the service was made. It was as if everyone who came in came prepared to enter into the spirit of the service and no instruction or ritual was necessary to guide them. It all flowed. As Elder Smith invited anyone who wished to testify, the rhythm swelled. A couple women went to the microphone to tell of their gratitude for making it through another week to join the faithful in the “House.” A young man who had been sitting silently in the left bank of chairs took up a bass drum and thumped out the low end, balancing the staccato of the clappers. Chorus gave way to new chorus as Elder Smith set a meditative tone. People entered through doors in every corner of the great room, taking up the beat. Horns emerged from cases in the front. First, a tuba played by a bearded young man played a call and response to Elder Smith. Men filled in the section of chairs, oiling trombone slides and greeting one another. As the horns unhurriedly prepared, the chorus and the clapping kept on. A man from the band pit approached the pulpit. He spoke of the joy of the spirit, and the strength that goes along with it. He asked us, would we rather be weak or strong.

“If you are weak, it is because you want to be weak. And if you are strong, it is because you want to be strong,” he said.

He told us to count ourselves fortunate for this moment we found ourselves in, that God did not have to wake us up that morning. Then he took up his horn and the music swelled to a euphoric crescendo.

HOP History

The United House of Prayer for All People was founded in 1919 in Wareham, Massachusetts by a Portuguese-speaking immigrant from Cape Verde named Marcelino Manuel de Graca. His name was anglicized to Charles Manuel Grace when he hit American shores. He became Bishop Grace after founding the United House of Prayer for All People. His followers still call him Sweet Daddy Grace.

Bishops hold the penultimate position in the church, something like pope in Catholicism. A Bishop is God’s instrument on Earth, an infallible tool in the hand of the Father. House of Prayer members refer to this principle as one-man leadership. Each subsequent Bishop after Daddy Grace has also borne the informal title of Daddy and carried the same authority, though they have been elected by church elders. Only Sweet Daddy Grace was self-appointed.

Daddy Bailey, 2008-Present

Daddy Grace spent over thirty years leading the denomination, planting churches from Beaufort to Buffalo. When his train pulled into the station in Charlotte, Augusta, Newport News there would be a parade waiting to usher him to a tent revival or church where he would gather his flock. These parades would include processions of the believers and, most importantly, an early incarnation of the shout bands that are peculiar to the House of Prayer.

“Praise ye the Lord.

Praise Him with the sound of the trumpet.

Praise Him with the psaltery and the harp.

Praise Him with timbrel and dance.

Praise Him with stringed instruments and organ.

Praise ye the Lord.”

Psalms 150

Since the 1920’s, House of Prayer services have included this incomparably ecstatic music. Daddy Grace deliberately employed large bands playing emotive, instrumental music to draw worshippers into “one accord” from the earliest days of his ministry. Bands were formed from the ranks of the faithful and, in the beginning, included all manner of instrumentation, from saxophones and mandolins to washboards and pipe organs. At some point, probably in the 1960’s, the trombone became the dominant instrument in the shout band. Legendary bands like McCullough’s Sons of Thunder (named for the second Bishop, Daddy McCullough) from the Harlem House of Prayer and The Happyland Band from Newport News, Virginia feature up to a dozen trombones, with most playing a melodic refrain while a leader plays improvised solos. The closest comparison to the music, stylistically, is early New Orleans jazz. Though no such direct comparison does justice to the singularity of the music in terms of rhythmic force and emotional fervor. The music of the shout bands can only truly be heard in the United House of Prayer for All People.

In a way, this is by design. For a HOP band to play outside of service, permission must be granted by a church elder. If the band is to be compensated for their performance, the proceeds are expected to benefit the church, never the musicians themselves. The bands have rarely been recorded.

This seemingly tight-fisted policy works toward an end, though. All church property, from the buildings and land containing the Houses to the apartments the church has built for some of its low-income members, is owned by the church free-and-clear, without mortgages. The policy goes back to Daddy Grace (as do most in the HOP) who was frequently called a charlatan for his insistence on tithing and his accumulation of wealth. But Sweet Daddy Grace also paid in full, and in cash, for the early churches he planted. To this day, the House of Prayer takes no loans and bears no debt.

This stalwart self-reliance could be the reason the HOP retains an air of mystery and exoticism to outsiders. I had passed the Greenville HOP on Pendleton Street many times and wondered at the name of the church and the eccentricity of the exterior. But it wasn’t until I spoke with State Representative Chandra Dillard about the music career of her father Moses that I began to learn what the HOP was all about.

The Dillard Family

Moses Dillard was a prolific multi-instrumentalist, producer, arranger and bandleader who emerged from Greenville and found himself at the epicenter of the soul, r’and’b and gospel music scenes from the ’60’s into the ‘80’s. Like so many other basal American musicians, he got his first musical training in the church. Church for the Dillard family had been the United House of Prayer since Sweet Daddy Grace first came to Greenville in the late 1920’s.

Today, Moses’ brother Mitchell holds the title Elder Dillard. He can be found dishing out food or tending to the property at the Pendleton Street House of Prayer most days. The church owns the retail property next door on Pendleton, and during my last visit, I followed Elder Dillard out to the parking lot to meet with a contractor whom he’d hired to mend a broken fence before sitting down to talk about the history of the HOP in Greenville and the Dillard family’s role therein.

The Dillard family is foundational to HOP history in Greenville. Elder Mitchell Dillard’s grandfather, Tom Dillard, joined in the beginning and was an Elder in the church all the way back in the 1940’s. Mitchell remembers fondly his grandfather’s old ways of doing things.

Tom Dillard was a farmer. Mitchell recalls riding around with him in his horse and buggy, selling the produce from his farm all around Greenville. In their travels, the grandfather would have the grandson read to him from the Bible. As young Mitchell read, he would skip over words that were outside his juvenile vocabulary. His grandfather never failed to catch him, remembering the word that had been omitted and instructing his grandson on its pronunciation and meaning.

“He could not read, but he had the Bible memorized, from Genesis to Revelations,” Mitchell Dillard marveled.

Mitchell and Moses nearly missed out on an HOP upbringing. Their dad spent some wayward years outside the church. But their mother was Methodist and insisted that her husband observe some kind of faith, so he returned to the HOP and took his sons with him.

The Dillard boys were taken with the infectious music they heard at their father’s church. Both Moses, Mitchell and their brother Daniel took up a horn. Moses, especially, embraced the musical nature of the service and excelled as a trombonist at a very early age. Mitchell recalls how the congregation marveled at his brother’s precocious ability.

Moses Branches Out

Moses picked up the guitar in his early teens and almost immediately displayed talent on that instrument, as well. He was taken under the wing of Bill Dover, who was the Sterling High School band director and made some side money playing local country clubs, weddings, and parties. From a young age Moses was out at night playing gigs and back at the HOP making a joyful noise on Sunday morning. Even so, all that work did not keep him from finishing high school and going onto South Carolina State University to earn a degree in music.

One can easily imagine that Moses Dillard would have been dissatisfied letting his remarkable talent languish in Greenville. The Dillard’s were a working-class African American family in South Carolina in the mid-20thcentury, after all. Even if he were on fire with the Spirit, the temptation to take such a potentially lucrative talent and use it for purposes other than bringing the believers into one accord would have been great. Moses Dillard clearly knew what he had and set out to make use of it.

Moses and young Mitchell took the music on the road. Mitchell became the driver and unofficial tour manager for Moses’ first couple bands. Over time, Moses assembled a cast of Greenville musicians that would go on to establish a broad range of careers in the music business; Jesse Boyce played with starts like Little Richard and Aretha Franklin, Leo Adams established several groups and helped build Greenville’s disco and funk scenes at Sundown Sound Studio, Otis Forrest became an established studio musician and arranged and produced in Nashville for decades. Peabo Bryson first took the stage with Tex-Town Display when he was just a teenager. First as the Dynamic Showmen and later as Tex-Town Display, Moses and his bands played on stages and records with the soul, jazz and gospel music legends of their day. They were the studio band at Amy/Mala/Bell Records, backing up James and Bobby Purify, Sam and Dave and others. They travelled to Chicago to play on Curtis Mayfield’s seminal track, Move On Up. They toured the world on a USO package with the first Miss Black America, Gloria O. Smith.

Moses settled into a studio career in Nashville in the 1980’s and produced the gospel stars of the time, including a Grammy award-winning album for the Rev. Al Green. Along with his music, Moses found his way back to the ministry, receiving a degree in divinity from Vanderbilt University.

Of course, gospel music has been an essential ingredient in the stew of American popular music all along. The singing styles of Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin are gospel as much as anything else. One sees a clear gospel thread running through country, blues, doo wop. And soul music just replaces Jesus with baby.

But the House of Prayer shout bands are an unpredictable, mutant hybrid within this cross-pollination. It’s hard to say what of popular and folk styles came together to create the shout band sound. One recognizes unmistakably American characteristics, but there is a feeling and a structure to House of Prayer music that comes from somewhere else. Perhaps something was transmuted from the Cape Verde Island heritage of Sweet Daddy Grace. It is hard to be sure.

It is not hard to be sure that the church encourages musical exploration in its members from an early age and fosters talent when it manifests. Several of the Dillard men who grew up in the church went on to lead musical lives. Moses and Mitchell’s brother Daniel played the saxophone and had gigs with Gladys Knight and many others. Henry “Buff” Dillard still plays the HOP mainstay, the trombone, and has a thriving music career in Charlotte.

“I can see the thread of the (HOP)) influence through all my Dillard side of the family. I have a little third cousin. He’s three years old. He’s playing a horn, y’all! And he’s a member of the United House of Prayer. So, I know where that thread comes from.” Said Rep. Dillard.

Lucky for us that the Dillard family chose to worship at the House of Prayer and that Moses Dillard’s talent revealed itself and was allowed to flourish. As a fan of the man’s music, I like to imagine the twelve-year-old boy swinging in praise to the Lord with his trombone.